The Vision for an Accurate, Modern English Bible Translation Becomes Reality

Howard Long had a problem—one that originated in 1611. He had shared the gospel with people before, and though many had trouble understanding the King James Version of the Bible, he had never experienced a reaction like this. As Long shut the door to his hotel room, he began to wonder what would have happened if he had had a different Bible, a Bible in modern English.

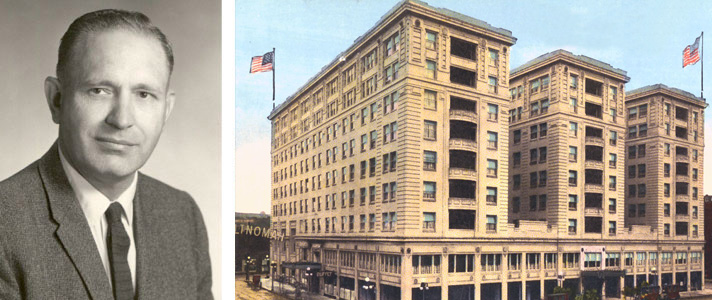

It was 1955, and Long was in Portland, Oregon, on business. An engineer and representative for General Electric, Long often made trips throughout the Northwest from his home in Seattle. On this particular visit, Long’s plans included dinner with a business associate at the Multnomah Hotel.

Long’s agenda was short: discuss GE’s latest engineering projects, and if there was an opportunity, the Christian faith. Conversations with Long often turned spiritual. A devoted believer, he wanted everyone he met to know and have a relationship with Jesus Christ.

On this particular evening, when his associate mentioned that he didn’t know too much about God, Long eagerly suggested that they take a look at what the Bible had to say on the topic.

Howard Long and the Hotel Multnomah in Portland, Oregon, where Long tried to share the Bible with a business associate.

God’s Word had been a vital part of Long’s life for decades, and he knew it could make an impact on this man’s life as well. But as he began to read, Long saw his associate’s face turn bright red. Thinking he had offended him, Long prepared for the outburst of anger that was sure to follow.

Instead, he watched dumbfounded as the man began to chuckle, then fall out of his chair in a fit of laughter. “That’s the funniest thing I’ve listened to in years!” the man said.

The opportunity to talk about Jesus was over. The verses that were holy and life-changing to Long were not only archaic and incomprehensible to his associate’s ears, they were hilarious.

Long had no formal seminary training. He was an engineer, an inventor, a pilot, a college physics instructor—a layperson who liked to share the gospel. But as he sat in his hotel room and pondered what had happened, Long’s opinions on biblical texts were becoming concrete and passionate. Something had to be done about the choice of Bibles in the 20th century. Modern people should be able to learn about God’s power, love and redemption from a Bible in up-to-date language.

As the champions of the Reformation had argued, if Jesus’ disciples heard his words in their own tongue, shouldn’t those who speak English be able to as well?

Making the Bible Accessible to Everyday Lay People

Long’s desire for a Bible in everyday language was not a novel idea. It was one that for centuries men and women had fought and died for. Prior to the late Middle Ages, few parts of the Bible existed in the vernacular. The Roman Catholic Church kept the Scriptures in Latin, though that had ceased to be the language of the people centuries before.

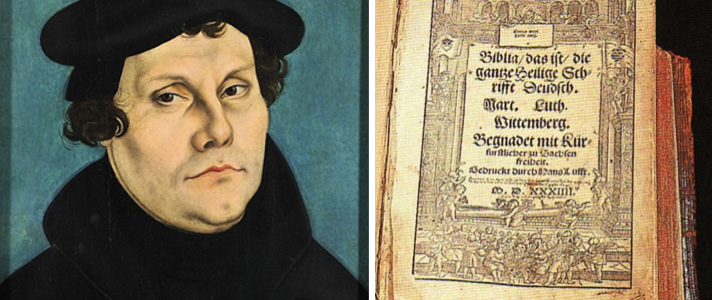

Martin Luther’s German translation of the Bible was published in 1534. Photo credit: “Lucas Cranach d.Ä. – Martin Luther, 1528 (Veste Coburg)” by Lucas Cranach the Elder.

In Britain, certain passages had been translated into Anglo-Saxon and Middle English over the centuries, but copies were rare. Before the invention of the printing press, all Bibles had to be transcribed by hand. Even copies of the Bible in Latin were scarce, and only members of the clergy or the extremely wealthy had access to them.

Early forerunners to the Protestant Reformation began to advocate the authority of Scripture over church teaching. They also began to translate the Bible into the language of the people, believing that everyone should be able to understand what the Bible had to say. John Wycliffe, an Oxford scholar, initiated the first translation of the entire text into English in the 1380s.

Translated from the Latin Vulgate, the Wycliffe Bible slowly spread throughout England, to the delight of the people but the horror of the church, which believed only priests had the special ability to decipher Scripture. Wycliffe was posthumously condemned for his efforts; church officials dug up his grave, burned his bones and threw the dust into the River Swift.

The people were hungry for a Bible they could understand, however, and demand for an English Bible persisted, no matter what church authorities preached.

Across Europe, scholars were translating the Bible into the vernacular, and with the advent of the printing press in 1450, scholarly and religious books could be produced more quickly and cheaply. By 1500, the Bible had been printed in German, French, Italian, Catalan, Czech, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese. However, these too were translations from the Latin, not from the original Greek and Hebrew.

After Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg in 1517, initiating the Protestant Reformation, he began work on a translation of the New Testament into German from the original Greek, believing that ordinary people needed an accurate, understandable version of the Scriptures. Afterward, Luther established a group of scholars to help with ongoing revisions to the New Testament and support the translation of the Old.

At the same time, an exiled English reformer named William Tyndale was also working on a translation from the Greek and Hebrew. By 1526, thousands of copies of Tyndale’s New Testament had come off the German presses and were smuggled into England hidden in bales of cloth, infuriating the church and state authorities.

Tyndale soon began working on the Old Testament while continuing to revise his New Testament translation, but before he could finish, Tyndale was captured, strangled and burned at the stake for his efforts.

Tyndale’s work would not disappear after his death. It informed several translations in the 1500s, including the Geneva Bible, as Protestantism was endorsed in England, then banned, then endorsed again.

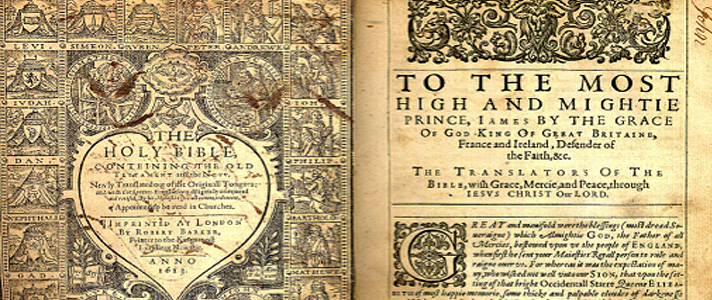

In response to a request for a new, official translation, King James I commissioned a group of 54 scholars in 1604 to produce what came to be known as the Authorized Bible, or the King James Bible. For the next seven years, translators consulted biblical texts in the original Greek and Hebrew, as well as other English translations, to produce a complete Bible that had the backing of the king.

“But how shall men meditate in that, which they cannot understand?” they wrote in the Bible’s preface. “How shall they understand that which is kept close in an unknown tongue?” They completed their work in 1611, and the result was a translation that was faithful to the Bible in the original languages and accessible to the people of England.

It was also beautiful. The scholars had a gift for not only translation but also the English language. They respected the style introduced by Tyndale and used much of the language from his translation. “Verily, verily, I say unto you, He that believeth on me hath everlasting life” (John 6:47). It was the speech people would later associate with Shakespeare.

King James Version, 1613 edition. Photo credit: King James Bible 1612-1613, Private Collection of S. Whitehead

Over the coming decades and centuries, the King James Version grew to become the world’s most beloved and bestselling English Bible. People came to see its phrases and style as the language of heaven.

But the translators never claimed their version was the definitive translation of the Bible. “Wee do not deny, nay wee affirme and avow, that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English, set foorth by men of our profession . . . containeth the word of God, nay is the word of God.”

However lovely it may be, language is not static. It shifts and changes as people and groups merge, new ideas are shared, and the pace of communication increases. The King James Version was frequently revised by printers to correct errors and slightly update the language, but the phrasing remained largely Elizabethan English.

The Revised Version of 1885 and its American edition, the American Standard Version of 1901, were intended to be revisions of and updates to the King James Version. But neither the RV nor the ASV gained wide acceptance because the language was pedantic and the translation woodenly literal.

In 1952, the Revised Standard Version appeared; however, it was a revision of the ASV, not a new translation. The RSV became standard in many mainline Protestant churches, but the sentiment among evangelicals was that it had problems that could not be overlooked. Most evangelical churches continued to use the KJV, seeing no acceptable alternative to the respected KJV translation.

A Bible for the People

Howard Long mulled over the incident at the Multnomah Hotel for months. Each time he thought about the versions of the Bible available to him, he grew more frustrated. Long grew up with the KJV Bible’s beautiful words and phrases, memorized them and came to cherish them. He had been frustrated with its older language when he evangelized or discussed Scripture with young children, but he had never felt his translation’s age as acutely as on that evening in Portland.

One day after church, his disappointment over the lack of an appropriate translation came out in a flood toward his pastor, Peter DeJong.

“We’ve translated the Bible into hundreds, thousands of tongues,” Long said. “And one day, when we run out of tongues, someone is going to translate the Bible into English!”

“If you feel so strongly about it, why don’t you do something about it?” DeJong replied.

DeJong agreed with Long. It was past time for a new translation of the Bible in contemporary English that was faithful to the original languages of the Bible, and he was prepared to help find a solution. But it would take 10 more years before the evangelical community would endorse efforts to produce the new translation.

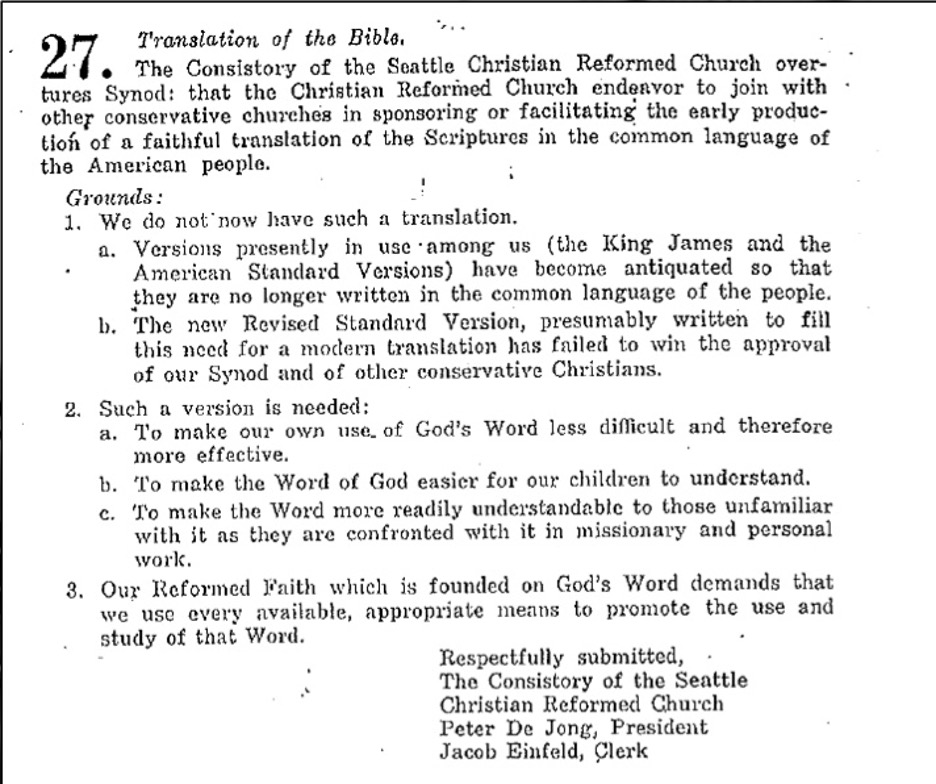

The two men knew they needed to first gain the support of their local church leadership. Long and DeJong were members of the Christian Reformed Church (CRC) tradition in Seattle. Process dictated the flow of ideas and proposals. With the support of elders and deacons, the proposal was taken forward to the denomination’s regional convention. But the proposal stalled—and failed.

No one was going to burn the representatives from Seattle at the stake for wanting a contemporary English translation, but the rest of the region did not recognize this as an urgent need.

The Seattle church’s overture failed to gain support at the regional level.

The church’s leadership was not about to let go of what it felt was an urgent necessity. It decided to bypass the regional group’s approval and go directly to the entire CRC denomination. It argued that the Bible’s message would be more effective if it was easier to understand.

“Our Reformed Faith, which is founded on God’s Word, demands that we use every available, appropriate means to promote the use and study of that Word,” the Seattle contingency wrote in its Overture to the Synod in 1956.

This time, the proposal struck a chord. The wider denomination was not happy with the recently released RSV Bible and was ready to consider alternatives. A committee of four professors from Calvin Seminary was commissioned to study the issue and investigate what it would take to issue a new translation.

Long, who hadn’t been able to attend the denominational meeting, told the CRC committee it would take at least a few million dollars to complete the project, but he wasn’t worried about finding the money. After all, Long would argue, what does Christianity need more: $100,000 pipe organs, or a Bible in the language of the common people?

The four scholars thought Christianity likely needed a new Bible but wanted to hear from other members of the evangelical community before pursing such an expensive idea. Extensive correspondence began between the committee and Bible scholars, Christian publishers, churches, Bible societies and missions organizations.

The National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), a group representing dozens of denominations and hundreds of other Christian organizations, received one of the letters asking about a new English version of the Bible and thought it worthwhile enough to form its own committee to investigate the issue. But neither the CRC nor the NEA group was in a rush. An undertaking of such gravity would require an extensive foundation of support, resources and talent.

The two groups finally came together in April 1961, recognizing that they would need to work closely to make meaningful progress. The NAE could summon the broader evangelical support necessary for such an endeavor, and the CRC was far ahead of the NAE in conducting the studies and research that were needed in order to begin a new translation.

In late 1962, their next step became clear. They would work to host a Bible conference made up of leading evangelical scholars, potential sponsors and endorsers.

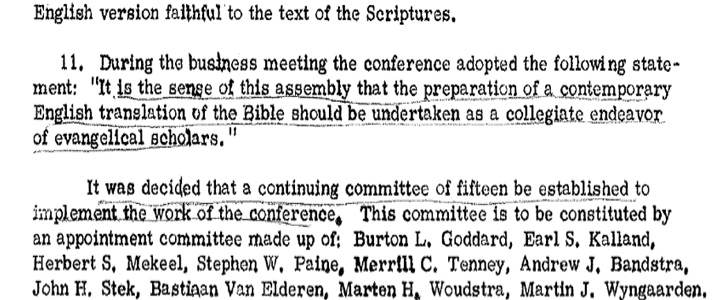

On August 26-27, 1965, a Bible translation conference was held at Trinity Christian College to consider whether or not the evangelical community should pursue a new, contemporary English translation of the Bible.

The Vision Becomes Reality

In August 1965, Christian scholars and leaders gathered for a two-day conference at Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, Illinois, to answer two questions:

- Is there truly a need for a modern English version of the Bible?

- If so, what should be done about it by the broader evangelical community?

Representatives from the Assemblies of God, Baptists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Methodists, Nazarenes, Mennonites and Christian Reformed denominations debated previously circulated white papers alongside members of the committee.

The consensus was that if they endorsed a new Bible translation, it would have to be for the entire English-speaking world, not just for Americans. It would need to be for personal and liturgical use, as well as for evangelism. Previous versions of the Bible might serve the same purposes, but of the top contenders, the ASV was too literal in its translation, creating an awkward and artificial English style, and the RSV too liberal in its interpretation and translation of the text.

On the afternoon of August 27, 1965, the attendees decided to move forward. “It is the sense of this assembly that the preparation of a contemporary English translation of the Bible should be undertaken as a collegiate endeavor of evangelical scholars.”

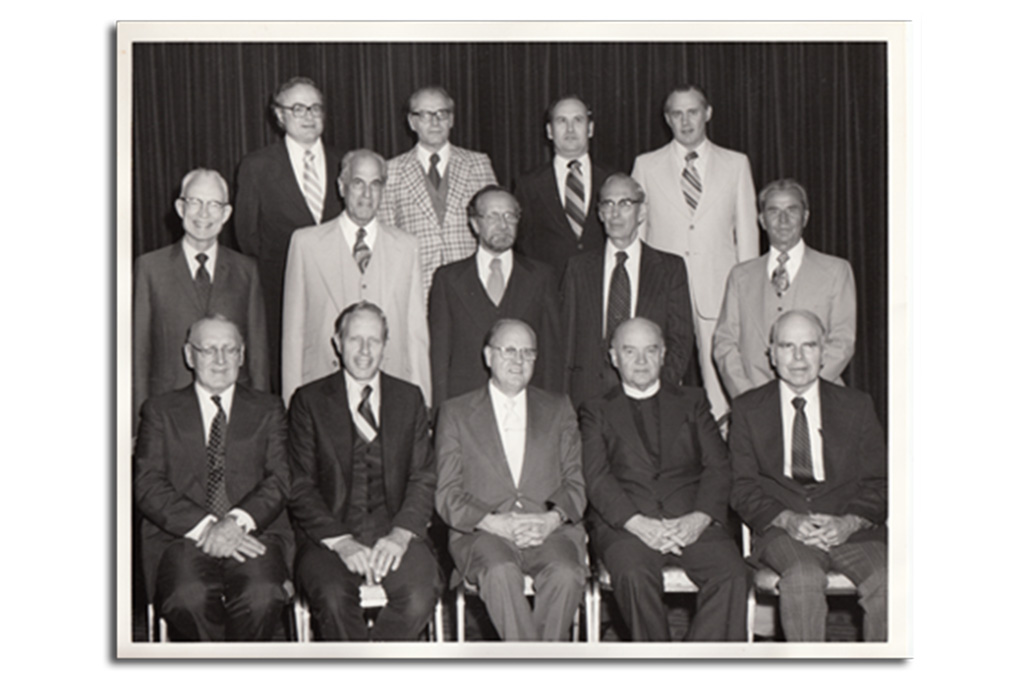

On August 27, 1965, the Bible Translation Conference commissioned a contemporary English translation of the Bible and a committee to oversee the work.

Howard Long’s vision was one step closer to reality. The broader evangelical community had just officially commissioned what would be known as the New International Version of the Bible.

A group of 15 scholars would take the mandate forward. Over the next 13 years, members of this Committee on Bible Translation devoted their lives to organizing and overseeing the massive task of translating the Bible into contemporary English.

They would call on the most respected evangelical scholars to begin afresh from the original Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic texts. They would consult with contemporary English-language experts on style. And in addition to ensuring that the text was accurate and comprehensible to modern readers, the CBT would help make certain that the text reflected the beauty and style of the Bible in the original languages.

The New York Bible Society (now known as Biblica) has distributed more than 650 million Bibles and biblical resources since its founding in 1809, including to immigrants at Ellis Island.

A Group Agrees to Fund the New Translation

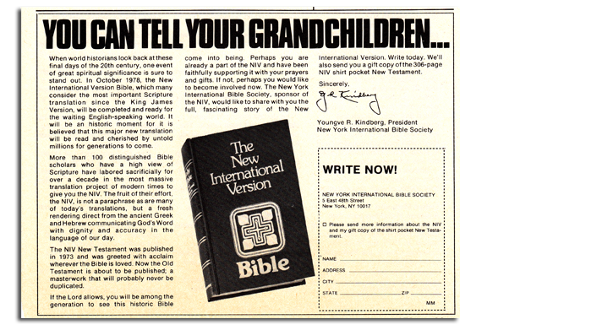

When New York Bible Society representatives Youngve Kindberg and Morris Townsend attended a meeting about the start of a new Bible translation in August 1966, it didn’t take them long to realize that they might have found a solution to a problem they were trying to solve – the society did not have a Bible in the language of one of its target audiences: people who speak contemporary English. Young people in particular were not connecting with the older King James Version that the society was distributing.

At the same time, the Committee on Bible Translation (CBT) was facing its own problem. A year earlier, it had been commissioned to produce an accurate and understandable version of the Bible in contemporary English but the project needed funding and was looking for supporters.

“We ought to do this,” Townsend told Kindberg after listening to the CBT’s translation plans.

Founded in 1809 to print and distribute Bibles in America’s largest city, the New York Bible Society (now Biblica) promoted the tenet that everyone should have access to the Bible in their native language. From its earliest days, the society helped fund translation work — beginning in 1810 with a gift of $1,000 toward William Carey’s translation of the Bible into Bengali — while remaining focused on distributing the Scriptures.

The society gave Bibles to the military beginning with the War of 1812, to inmates, to seamen passing through the city’s busy ports, and to immigrants arriving at Ellis Island. Hospitals, hotels, colleges, taxis, and even the subway and Long Island beaches had also been distribution points over the years. By the 1960s, the society had given away tens of millions of Bibles.

After the August 1966 meeting, Kindberg couldn’t get the idea of a new translation out of his mind or his prayers. On the surface, such a financial commitment didn’t make sense. The society’s resources were limited. It had just increased programming and staffing.

But the need was too great to ignore. He and Townsend went to the society’s board of directors, who agreed to keep the idea on the table and continue in prayer. Proceeding cautiously, the society began discussions about planning and budgeting with the CBT.

In January 1968, the New York Bible Society formally agreed to fund the efforts to produce a new version of the Bible in contemporary English, beginning with a budget of $100,000 for the first year. The society would hold the copyright but would not be able to touch the text, which would be under the jurisdiction of the CBT.

Escalating Costs Nearly Derail the NIV

It was a good thing the New York Bible Society had no idea what the final price tag would be for a contemporary English translation of the Bible. If it had, the society might never have agreed to fund the project, which ultimately cost more than $2 million.

The Committee on Bible Translation (CBT) and the society had done studies to determine what it would take to complete the work, estimating costs at $850,000. Such a cost would stretch the modest-sized Bible organization. But the society believed in the translation and was determined to help make it possible.

Everyone knew that translating the Bible was an enormous task. Nevertheless, it became apparent early on that doing it well would take longer than planned. By the end of 1975, the translation costs had topped $1.26 million, and the Old Testament was still several years away from completion.

The society could not keep up with costs. Its already small staff had been reduced by half. The core endowment from its 1909 centennial campaign had dwindled, and double-digit inflation took its toll on what was left. Board members had even taken out second mortgages on their homes to help with costs.

The New York Bible Society (now Biblica) ran ads in Christian publications asking for financial support for the NIV translation.

The CBT had tried to help with fundraising along the way. A few years earlier, the executive secretary of the CBT, Ed Palmer, started the 450 Club. He hoped to find 450 people who would agree to donate $250 a year for the next four years to the effort, but only 30 people responded.

The New York Bible Society told the CBT in November 1975 that the next step was potential cancellation of the Old Testament translation. The committee put measures in place to work more quickly, but the new translation still urgently needed funding.

In early 1976, the New York Bible Society’s president, Youngve Kindberg, decided to approach Zondervan. The CBT had asked Zondervan Publishing for funding before the New York Bible Society stepped in. At that time, the publisher had declined, unsure of the need for a new Bible. By 1971, however, Zondervan trusted that this new translation would benefit all believers and agreed to become the sole American licensee. It published the New Testament: The New International Version in 1973.

Kindberg and the Bible society asked the publisher for additional advances on the Bible’s royalties in order to complete the translation of the full Bible.

“By this time,” founder Pat Zondervan said, “we were so enthusiastic about the potential of blessing that this new translation would bring that we wanted to do all that we could to assist in the underwriting of the expense.” Zondervan offered to advance up to $250,000 in royalties through 1978.

The work could continue.

To raise additional funds, the New York Bible Society sold its beloved New York City building in the midst of a buyer’s market. The neo-Gothic structure at 5 East 48th St. had been honored by the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects when it was completed in 1921. The society moved from New York to East Brunswick, New Jersey. It had sacrificed almost everything.

Known today as Biblica, the ministry works in 55 countries and continues to fund the translation and publication of Bibles in the world’s leading 100 languages so that billions of people can experience the life-transforming power of the Scriptures in their native language.

And the fruit of the combined labor of the New York Bible Society, the CBT, and Zondervan, is a translation that is known and trusted around the world for its accuracy, beauty, and clarity.