Where Did the NIV Come From?

Transcript

This morning, I want to tell you a story of God’s grace. It’s an amazing and true story of how God has used imperfect people, imperfect processes, and imperfect institutions to do something extraordinary. The story begins with one faithful Christian man named Howard Long. Howard Long was not a scholar. Howard Long was not a theologian. Howard Long was not an ordained minister. Howard was simply a Christian businessman who worked for General Electric and who attended a CRC church in Seattle, Washington. Howard’s job required him to travel around the country, and because he took the Great Commission seriously, whenever he did travel, he made it a point to talk to people about the Gospel of Jesus Christ. When he would do that, he would read from the bible, the King James Version of the bible; but Howard was becoming increasingly frustrated in his evangelistic efforts because the words of the King James Version were becoming more and more incomprehensible to the people he was sharing them with.

It all came to a head for Howard in a business meeting that took him to Portland, Oregon, in 1955. He was having dinner at the Multnomah Hotel, and he was reading the King James Version to a man he had met, trying to communicate the Gospel. When Howard looked up from reading the text, he saw the man get red in the face and then just burst out laughing. The man was not reacting to the content so much as he was the wording of what he just heard. He told Howard that was the strangest sounding English he had ever heard. So a frustrated Howard Long went back home to his CRC church in Seattle and complained to his pastor, Rev. Peter DeYoung. Howard said, and this his quote, “We translated the bible into hundreds, a couple of thousands tongues, and when we run out of tongues to translate it into, someday we are going to translate it into English.” Howard’s pastor agreed that he had a point, so Pastor Peter DeYoung and the consistory wrote up an overture that they wanted their classis to send to the annual synod of the CRC. The overture recommended, this is another quote, “That the Christian Reformed Church endeavor to join with other conservative churches in sponsoring or facilitating the early production of a faithful translation of Scriptures in the common language of the American people.”

Fantastic, and yet incomprehensibly, the classis did not approve this proposal. But God’s thoughts are not our thoughts, and his ways are not our ways. Howard Long’s pastor and consistory didn’t give up. They exercised the right that they had to bypass classis and take their overture directly to Synod where we have it duly recorded in our Acts of Synod. So it was that the delegates to the CRC Synod of 1956 were faced with a decision that would have tremendous implications. One highly effective delaying strategy that is often used in such situations is the appointing of a study committee. (laughter) So our Acts of Synod 1956 – here it is, it’s recorded right in our history – records the decision to refer this entire issue to a study committee made up of “the teaching staff of the Old and New Testament Departments of our seminary for thorough consideration and report to the Synod of 1957.” That teaching staff included four men: Henry Schultze, Ralph Stob, Martin Wyngaarden, and Marten Woudstra.

Maybe Synod thought that passing this matter off to a small committee of four men, well that would be an easy way to make the whole matter disappear after a while. But God’s thoughts are not our thoughts, and his ways are not our ways. As everyone here in this room would surely agree, the study committee consisting of the faculty of the Old and New Testament Departments of Calvin Seminary would surely do the right thing, and they did. The recommended that Synod endorse this overture and establish a committee to begin carrying it out. Good old faculty, and their recommendation is recorded for us in our Acts of Synod 1957. You can check it out. It is a little dusty, but it’s in there.

As you may know, every Synod has an advisory committee. You’re right to laugh (laughter). These advisory committees screen the recommendations that all the study committees make, and they recommend bringing to the table only those that they approve. You guessed it. The advisory committee of the Synod of 1957 did not approve this study committee’s recommendation. They argued that the study committee had not demonstrated an urgent necessity for a new translation, and they had not demonstrated “that there are sufficient conservative churches interested in this project.” So the initiative for a new English translation in the common language of the American people almost died on the vine once again. But God’s thoughts are not our thoughts, and his ways are not our ways.

There was, among the delegates to that Synod of 1957, a man whom God had raised up for just a time as this. Some of you will recognize his name. His relatives are here this morning. His name was John Stek. John Stek shrewdly argued to Synod. He said, “Wait a second, Synod also gave the task to that study committee that they should receive input from other faith communions regarding the legitimacy of this project, whether they were interested in it, thought it was a good idea, would be willing to participate in it. You know, we haven’t really received much of that input yet. So wouldn’t it be premature for Synod to make a decision before we had received that input?” Any of you who knew John would be able to agree that he could be very persuasive, and he carried the day. John Stek saved this idea at Synod, and so Synod decided to defer the decision on this matter until the following year.

That input from other faith communities began to come in, and it was very enthusiastically encouraging. So the Synod of 1958 finally approved the study committee’s recommendation and decided to go ahead with the project. So they told that study committee, consisting of those four members of the faculty of the Old and New Testament Departments, yeah, I guess it’s an okay idea. Why don’t you see about making it happen.

Well, these guys already had full-time jobs, right? They’re church men, bible teachers. They don’t know too much about bible translation. What about the processes, the resource? What all is involved? What do we need to consider? Because of their commitment to the Word of God, they committed themselves to do this. They began laying the groundwork. They engaged in discussions with the National Association of Evangelicals. They made contacts with other evangelical scholars who were similarly committed to working toward the production of a new English translation of the bible.

Finally, in 1965, seven years after the Synod of 1958 had given its go-ahead, a multi-denominational gathering of Christian leaders and scholars met for a two-day conference at Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, Illinois. They made this recommendation: “It is the sense of this assembly that the preparation of a contemporary English translation of the bible should be undertaken as a collegiate endeavor of evangelical scholars.” That statement marks the formal commissioning of what would eventually be called the New International Version of the bible, and it’s the anniversary of this commissioning that we celebrate this year, the fiftieth anniversary.

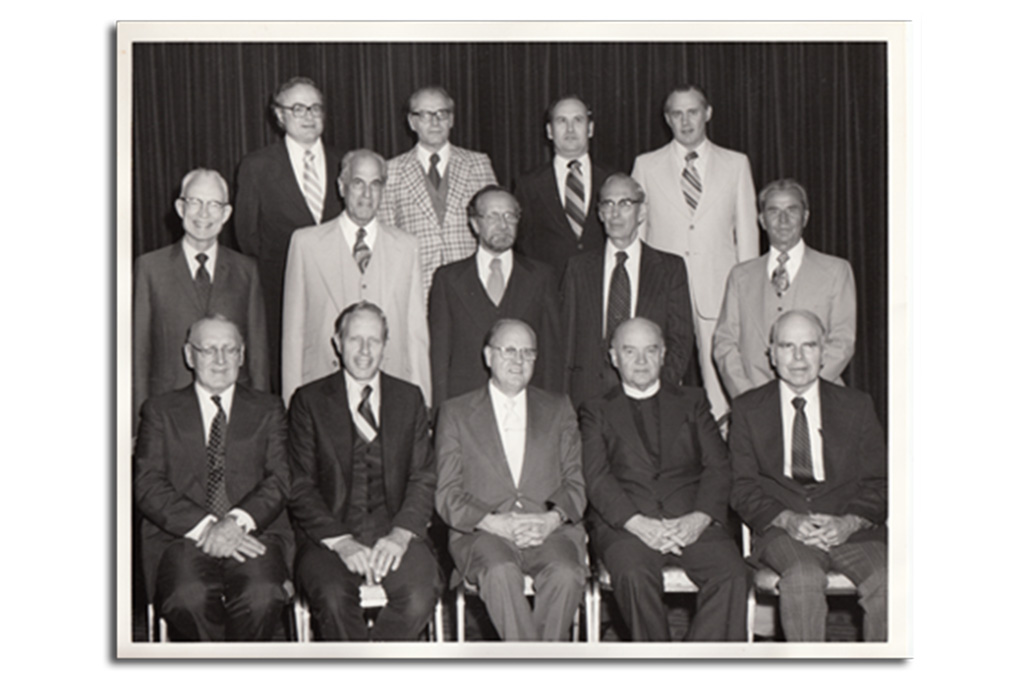

So a committee was formed to select fifteen scholars from across the evangelical spectrum who would do the actual work of the translation. The committee that was going to be choosing these people consisted of Andy Bandstra, John Stek, Bastiann Van Elderen, Marten Woudstra, and Martin Wyngaarden, all professors at Calvin Seminary. They selected a group of fifteen translators called the Committee on Bible Translation. That committee included John Stek and Marten Woudstra also, and the work of the translation began, but where was the money going to come from?

This was a huge ecumenical project. It seemed as though the whole venture might collapse for a simple lack of funds. But God’s thoughts are not our thoughts, and his ways are not our ways. In God’s providence, the New York Bible Society volunteered to underwrite the entire project up to $850,000 that in 1967 it was estimated that it would cost to complete the project. So the translation work proceeded, but this was before computers. There was such a time. (laughter) The work was being done in longhand very carefully. It was taking a long, long time, and the U.S. economy at that time was in bad shape. It was a bear market, double-digit inflation. By 1975, the cost for the project had already well exceeded the original $850,000 estimate and had already reached $1.26 million, and the Old Testament wasn’t even completed yet. In order to make up the difference, the members of the New York Bible Society who were so committed to this task took drastic steps. They sold their historic New York City office building and moved to cheaper quarters in New Jersey. The laid off one-half of their staff. They got as many loans as they could from banks who were willing, and they even took out second mortgages on their family homes. These guys were putting their lives on the line, and still the costs mounted. There wasn’t enough to cover the shortfall. But then again in God’s providence, Zondervan Publishing House promised to give an enormous advance on anticipated royalties, anticipated royalties, so that the translation could be completed. So, they too were willing to place themselves in financial peril because of their commitment to the Word of God.

Finally, in 1978, the entire text of the NIV, Old Testament and New Testament, was completed and published. It is now read and used by almost half a billion people – that’s billion with a B – half a billion people throughout the English speaking world. That is how God used the evangelistic zeal of a single, faithful Christian man in a tiny denomination to have an effect on the whole world.

God also used this translation to touch my life at every point. 1956. The year that the overture of Howard Long’s consistory first made its way to Synod, that’s they year I was born. The year of my second birth, when I became a Christian and entered into a Christian bookstore for the first time in my life to buy a complete bible, that year was 1978. There is front of me was a brand new English translation of the bible. It’s a little battered, but here it is, produced by leading evangelical scholars and written in words that I as a new believer could understand. Years later, I was hired by Calvin Seminary and here I met a remarkable man named John Stek who nominated me to become a member of the Committee on Bible Translation in 2005. So, now I have the privilege of meeting every year with that diverse group of evangelical scholars to ensure that the Word of God continues to be accurately translated into contemporary English so that people like Howard Long can continue to use it to share the Good News of Jesus Christ, but people need to hear it in words they can understand. God’s grace is powerful, God’s grace is relentless, and God’s grace is unstoppable. Let’s pray.

Our gracious God, we thank you that your thoughts are not our thoughts and that your ways are not our ways. You use broken, faulty, imperfect people and processes to bring yourself glory. Please grant us the courage and commitment of our brothers and sisters who have gone on before us and to whom we owe a tremendous debt of gratitude. May we, like them, be wholly committed to communicating your Word to all those who are still in the darkness because we ask this in the name of the incarnate Word, our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

Dr. Michael Williams is professor of Old Testament at Calvin Theological Seminary and a member of the NIV Committee on Bible Translation.